2025 Year in review

2025 has been a turbulent year for international development. Aid budgets shrank, climate finance demands surged, and political pressure on development agencies – particularly in the United States – intensified. At the same time, global processes such as FfD4 risked sidelining transparency just when accountability and evidence are most urgently needed. Against this backdrop, Publish What You Fund redoubled its efforts to defend open data, strengthen transparency norms, and equip policymakers, civil society and citizens with the information they need to protect development effectiveness.

We began the year by expanding access to open aid information. Our new free training series – an introduction to using international aid and development data – helped over 200 practitioners in 48 countries uncover who is funding what, where, and with what results.

Transparency remained at the heart of our advocacy. In early 2025, we highlighted growing threats to the integrity of US foreign assistance data, as key platforms and datasets were dismantled, and produced new guidance on where to find USAID data. We also defended USAID against waves of misinformation, stressing that open data is one of the strongest tools for safeguarding truth.

We launched our 2025-2030 strategy – an ambitious plan to make aid transparency bigger, better and louder. This commitment shaped our interventions throughout the year, from climate finance to development finance institutions (DFIs) to localisation.

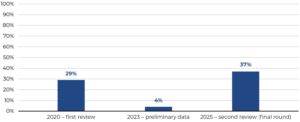

In June we launched the 2025 DFI Transparency Index, which saw near-universal improvement since 2023. Top performers included the World Bank, Asian Development Bank and African Development Bank, though persistent gaps remained in climate finance, private capital mobilisation (PCM), and community disclosure. Notably, IDB Invest became the first DFI to fully meet our PCM transparency test, and Development Bank of Latin America and the Caribbean (CAF) began publishing PCM data for the first time. We also shone a spotlight on seven DFIs that remain too opaque to assess – highlighting the urgency of raising standards across the sector.

Transparency is fundamental for ensuring that increasingly scarce aid is directed where it delivers clear, demonstrable value. Our Making Additionality Count paper examined how DFIs demonstrate that their use of Official Development Assistance (ODA) for private sector investments generates development or financial outcomes that would not be realised through the market alone. We found that many DFIs fall short on transparency – using vague, inconsistent or incomplete justifications for how their investments are additional.

In the autumn we celebrated a transparency win. After years of patient technical work by the Global Emerging Markets (GEMs) Risk Database team and support and advocacy from diverse groups – including Publish What You Fund and William Perraudin of Risk Control – a significant breakthrough was achieved. S&P Global Ratings announced that it had revised its approach to assessing the risk associated with sovereign operations by MDBs. S&P estimates that the change, made possible by the public release of the increasingly granular GEMs data, could free up between $600 billion and $800 billion of MDB capital over the next decade.

On climate finance, we released Better Data for Better Outcomes, assessing the transparency of the four largest climate funds. While the funds performed well on their own websites, only one – the Global Environment Facility – published open data to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) Standard. We followed this with Behind the Billions, a groundbreaking dataset revealing a $54 billion gap between multilateral development banks’ (MDBs’) reported climate finance and the project-level data available to the public. As the world’s focus moves to a $300 billion annual climate finance target, our analysis provided essential evidence on what is known – and what remains hidden.

In the aid sector more broadly, we continued to follow the money. Our Metrics Matter III research revealed that only 5.5% of project-type funding from five major donors went directly to local organisations – far below stated commitments. We also turned our attention to the 26 foundations that endorsed the Donor Statement on Supporting Locally Led Development. While we applauded their pledge to increase direct funding to local organisations, our report, Promises Versus Progress found that the vast majority have failed to report targets or progress. Without transparency, we don’t know if these promises are turning into real impact.

These analyses catalysed a wider conversation on the future of localisation, culminating in our Localisation Re-imagined event, which brought together local leaders, funders and policy experts to rethink power and accountability in the system. It also gave us the opportunity to speak on an OECD panel about how to measure locally led development.

Within the UK, our review of ODA transparency found overall improvements across government departments – but also a worrying decline in transparency at the Home Office, despite its substantial aid budget. We also looked into the transparency of Scottish aid funding, and submitted contributions to the Cross-Party Group on International Developments review into the Scottish Government’s international development funding. We were pleased to see its findings included our proposal that the Scottish Government should adopt the IATI standard.

We continued to track how global aid data is used by researchers, policy makers, CSOs and the media. And we analysed and applied this data to map global funding to end child marriage for Girls Not Brides.

We also broadened our transparency lens beyond ODA, calling attention to the growing scale – and opacity – of non-ODA financial flows. Our work underscored that without visibility across the full ecosystem of development finance, good decision-making is impossible.

Finally, we opened participation in the 2026 Aid Transparency Index to a wider group of organisations than ever before, strengthening this global benchmark and ensuring its long-term sustainability. Fifteen organisations have already signed up to be part of the accreditation and assessment process.

Across a year defined by shrinking budgets, rising needs and political headwinds, our work remained anchored in one conviction: transparency is the foundation of accountability, effective spending and public trust. In 2025, we hope we have helped to keep that foundation strong.