The transparency gap: Why can’t we assess the transparency of some of the world’s largest DFIs?

Inclusion in our DFI Transparency Index is based on criteria developed over the past five years and includes most of the world’s leading bilateral and multilateral development finance institutions (DFIs), assessing both sovereign and non-sovereign portfolios. However, a group of seven bilateral East Asian DFIs with substantial assets are not included. Why? The top line answer is that their levels of transparency are so low that no meaningful assessment is possible.

Since 2023, DFIs included in the Index have faced growing pressure to improve their disclosure. In our upcoming 2025 DFI Transparency Index we will measure progress since the inaugural edition. However, despite managing substantial assets, some unassessed DFIs offer almost no transparency, providing stakeholders with little insight into their investments. A recurring question we have faced, also raised by many we have engaged with, is why some of the world’s largest DFIs remain excluded from this scrutiny.

When setting the Index selection criteria, we were confronted with the reality that these institutions, despite managing trillions of dollars in assets, do not publish even the most basic disclosures needed for assessment. This lack of granular investment data from some of the world’s largest DFIs on transparency is not just a technical gap – it has real world consequences. These institutions manage vast sums of development finance, shaping economies, influencing markets and impacting communities.

As resources shift, with potentially fewer coming from the US and more from China and other donors, the lack of basic transparency means these unassessed DFIs are not only excluded from accountability mechanisms, but also miss opportunities for coordination, shared learning, and more strategic use of resources. This increases the risk of duplication, inefficiency, and even contradictory investments, while making it impossible for stakeholders to ensure that development finance is serving its intended purpose.

This blog explores which DFIs remain unassessed, the scale at which they operate, and where their disclosure practices fall short. We call for greater scrutiny of these institutions, urging them to improve their transparency and align with global best practices.

Unassessed DFIs make up a large proportion of global development finance spending

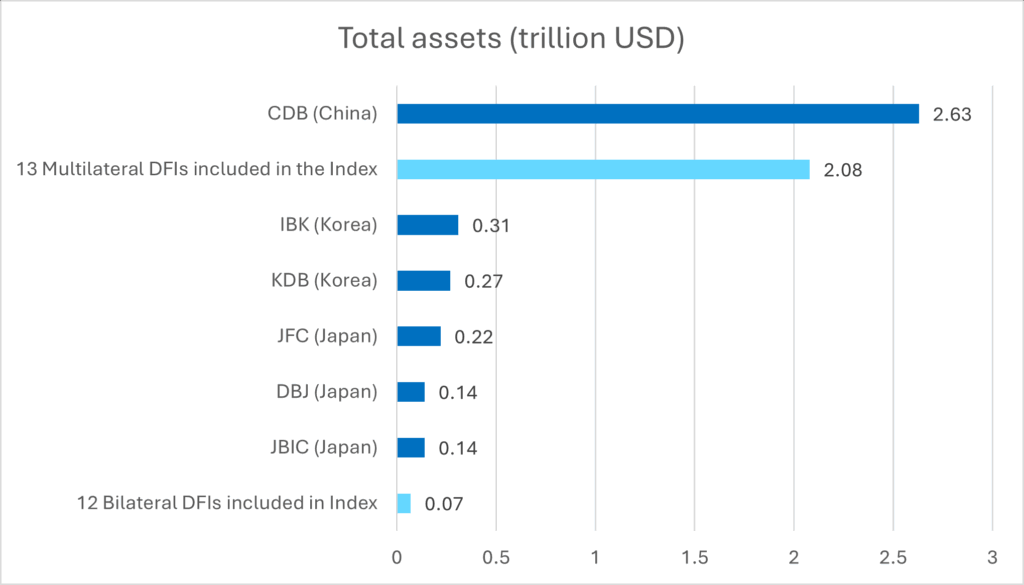

Seven large bilateral DFIs that are not included in the Index – China Development Bank (CDB), Industrial Bank of Korea (IBK), Korean Development Bank (KDB), Japan Finance Corporation (JFC), Development Bank of Japan (DBJ), Silk Road Fund (SRF) and Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) – have a combined total asset size of at least $3.86 trillion.[1] As a comparison, the bilateral DFIs that are included in the Index have a combined total asset size of $71.2 billion and the included multilateral DFIs have a combined total asset size of $2.08 trillion.

Consequently, this group of large DFIs collectively holds more assets than all the DFIs assessed in the DFI Transparency Index combined – with China Development Bank alone surpassing the total. Even without including CDB, the combined assets of the remaining five banks where data is available (JBIC, DBJ, JFC, KDB, and IBK) are still equivalent to around half the total assets of all the institutions currently assessed in the DFI Index[2].

Figure 1: Total assets of unassessed DFIs and combined assets of bilateral and multilateral DFIs included in the Index. Source: Peking University Institute of New Structural Economics.

It is important to note that a share of these bilateral institutions’ investments is domestically focused. For example, CDB’s disaggregated investment data is limited, but AidData (2021) reports $7.93 billion in overseas commitments,[3] while CDB’s annual report lists $1.83 trillion in gross loans and advances to clients.[4] However, the AidData figures remain the most detailed public information available on CDB’s financing, so it is not possible to more accurately determine the exact domestic-international split. Given the sheer scale of these institutions, however, we can assume that their overseas investments still constitute a significant share of overall development finance spending. This reflects the broader challenge of accessing even basic information on unassessed DFIs’ portfolios, including scale, geography and investment type, and underscores the core problem that a lack of transparency prevents meaningful scrutiny.

How unassessed DFIs perform across eight key aspects of disclosure

Given their significant share of development finance spending, we did undertake a basic assessment of what investment and policy information these institutions disclose. Figure 2 takes a closer look at each institution, highlighting that while most fail to disclose disaggregated project-level data, some information is published. We reviewed eight key aspects of basic transparency for each organisation which provides some assessment of general trends. These eight aspects were selected because our previous research has shown that key documents such as annual reports and Environmental and Social policies, as well as features like a centralised project database, represent the basic building blocks of transparency. These elements are essential for enabling more meaningful disclosure over time.

Figure 2: Matrix showing how unassessed DFIs perform across eight key aspects of disclosure

| CBD | IBK | KDB | JFC | DBJ | JBIC | SRF | |

|

Annual report |

|

||||||

|

Database |

|||||||

|

Project identification |

|||||||

|

E&S policy |

|||||||

|

Disclosure policy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Impact measurement approach |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Financial statement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IATI reporting |

|

|

Except for the SRF, all the unassessed DFIs publish annual reports and audited financial statements, offering a basic level of transparency on their overall financial activities. These reports typically provide high-level, backward-looking summaries of how funds were allocated over the past year, often including financial performance data, governance information, and in some cases, sustainability reporting. However, they do not disclose comprehensive project-level data, making it difficult to assess how investments are distributed or their specific impact.

IBK, KDB, DBJ and JBIC all disclose an Environmental and Social policy document, outlining their commitments to managing environmental and social risks in their investments. While these signal a policy commitment to responsible investment, the lack of detailed project-level disclosures makes it difficult to assess how these policies are applied in practice. What is needed, then, is systematic reporting on individual projects and their associated environmental and social risks.

A call for more scrutiny on unassessed institutions

One key requirement for inclusion in the Index is that DFIs demonstrate a fundamental commitment to transparency by maintaining a publicly available database or list of active investments. As our assessment relies entirely on publicly accessible information, DFIs that do not have a centralised and updated source of project-level data cannot be evaluated for their levels of transparency across key indicators. Furthermore, the Index assesses sovereign and non-sovereign portfolios and ranks them separately. Without clear distinctions between sovereign and non-sovereign operations, it is impossible to accurately compare the portfolios to other DFIs’ portfolios where these operations are clearly separate in their disclosures.

Beyond the scope of the Index, the inability to assess some of the world’s largest DFIs on transparency is not just a technical gap, it has real-world consequences. First, these institutions are increasingly managing vast sums of development finance, shaping economies, influencing markets, and impacting communities. As the development finance landscape shifts away from prioritising ODA and increasingly relies on other sources, the relative scale of these unassessed DFIs combined with their lack of basic investment data makes it much harder to carry out serious analysis of overall financial flows. Second, without clear public disclosures, stakeholders – including governments, civil society and affected communities – cannot track where and how funds are being used, evaluate their effectiveness, or ensure they align with development priorities and social and environmental safeguards. Finally, greater transparency is both a valuable internal management tool as well as a means to enable more effective collaboration with other institutions.

Initial steps for greater disclosure for these DFIs include:

- Publishing a centralised database of active investments

- Publishing project-level disaggregated data to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) standard

- Adopting an access to information policy

- Disclosing an impact measurement approach

Transparency isn’t optional, it’s essential. We stand ready to help.

Sign up here to join the launch of the 2025 DFI Transparency Index on 26 June at 2.30pm BST in london and online.

[1] Peking University (2024). Public Development Banks and Development Financing Institutions Database. Available at: http://www.dfidatabase.pku.edu.cn/DataVisualization/index.htm [Accessed 6th Mark 2025]. Note: Silk Road Fund assets are marked as N/A so are excluded from this figure. Database last updated September 2024.

[2] JBIC, DBJ, JFC, KDB and IBK have a combined total asset size of $1.08 billion and all DFIs included in the Index have a combined total asset size of $2.15 billion.

[3] https://china.aiddata.org/

[4] China Development Bank (2021). Annual Report. Available at: https://www.cdb.com.cn/English/bgxz/ndbg/ndbg2021/